Inorganic Cation and Anion Analysis

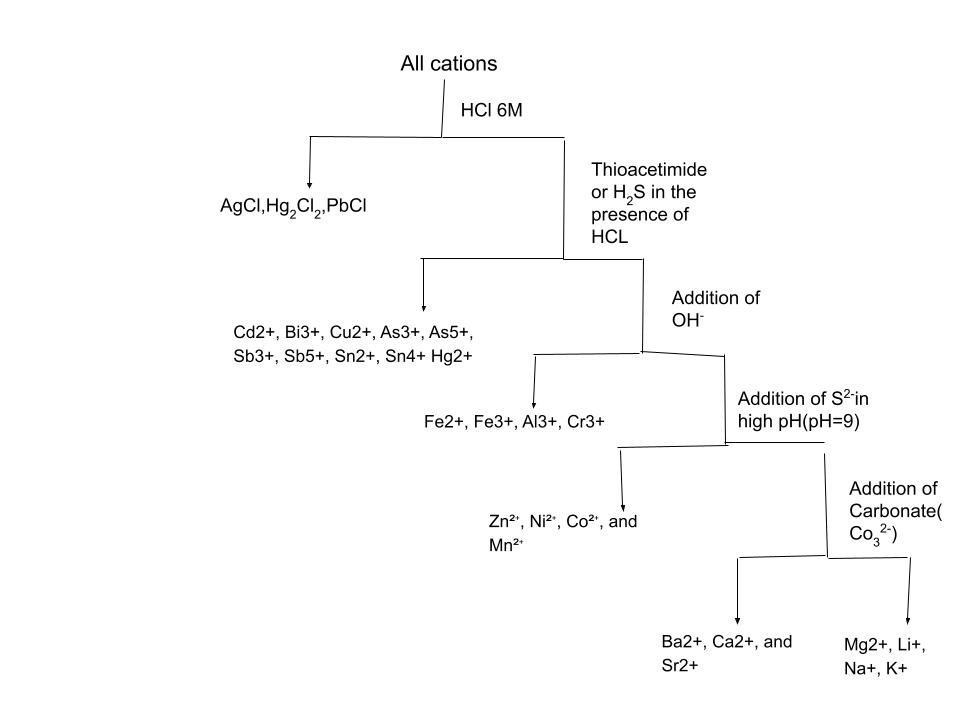

Ion analysis is a central practice in inorganic chemistry that focuses on understanding how individual ions behave in solution and how those behaviors can be used to identify and separate them. Rather than relying solely on numerical measurements or instrumental readouts, ion analysis is grounded in direct chemical observation: the formation of precipitates, changes in solubility, color transformations, complex-ion formation, and redox reactions. Each step narrows the field, allowing specific ions to be isolated and confirmed through characteristic reactions. This approach emphasizes chemical reasoning over memorization, requiring an understanding of why ions precipitate, dissolve, or transform under particular conditions. Sometimes more advanced methods like mass spectroscopy and UV-Vis are used but this qualitative method is also really important. Understanding the chemical reasoning behind each step will improve your chemical abilities a ton. Below is the overall scheme for how qualitative cation analysis is performed.

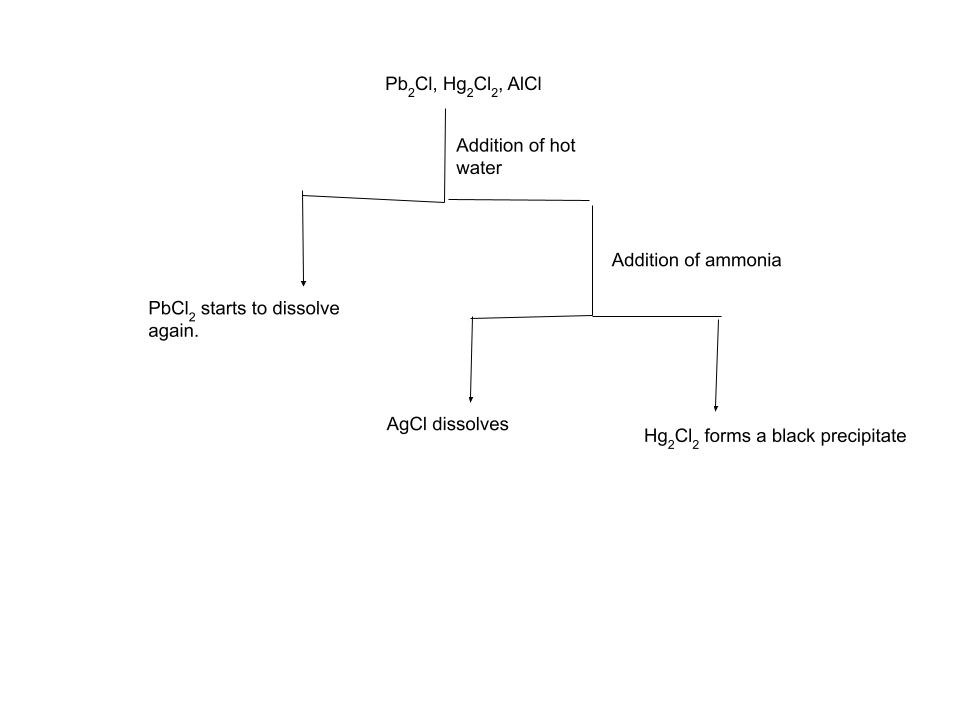

The first step is to add 1-2M of HCl to precipitate out AlCl, PbCl₂, and Hg₂Cl₂. All these precipitates are unfortunately white so it is difficult to figure out what ion we really have. Recall that as PbCl₂ becomes more soluble as the temperature goes up, so we can use hot water and if the precipitate dissolves then it is PbCl₂! Another thing about PbCl₂ is very sensitive towards the concentration of Cl⁻ because of its ability to form a complex ion. Sometimes the precipitation is unnoticeable and this is why Pb²⁺ is also considered for other groups too. If the precipitate is still present then we introduce NH₃ to the solution which causes the AgCl to redissolve and Hg₂Cl₂ to form a black precipitate formed with chloro-mercuric amide and elemental mercury.

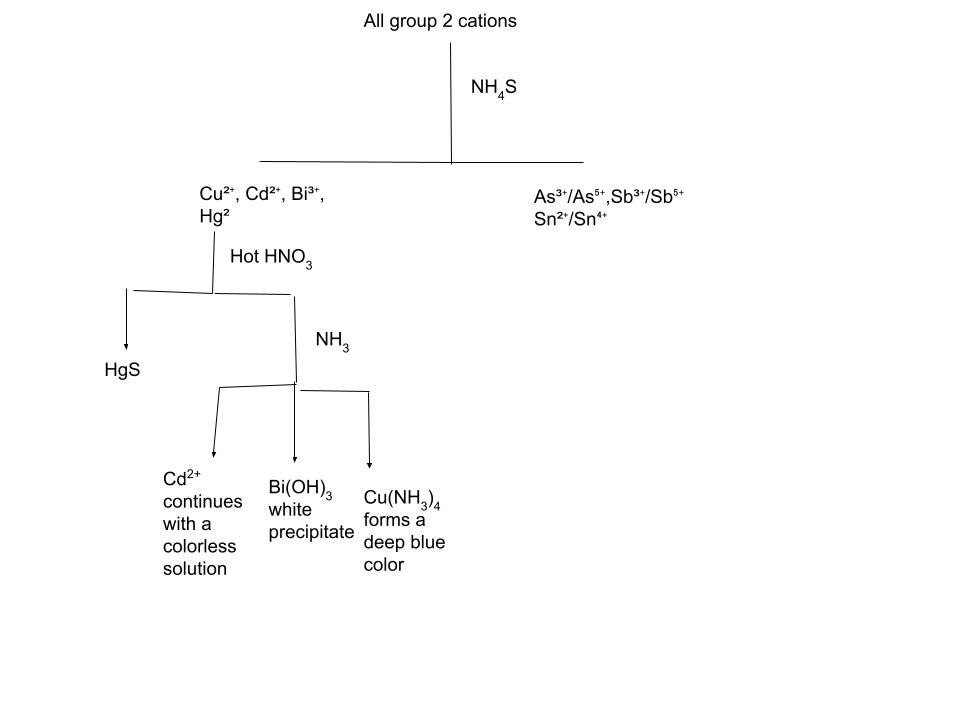

The second step of classical cationic analysis involves ions that form insoluble sulfides in acidic solution. These include Cd²⁺, Cu²⁺, Bi³⁺, Hg²⁺, As³⁺/As⁵⁺, Sb³⁺/Sb⁵⁺, and Sn²⁺/Sn⁴⁺. Since the sulfide ion concentration must be carefully controlled, hydrogen sulfide (or thioacetamide as a safer substitute) is introduced in the presence of dilute hydrochloric acid. H₂S is a gas so in order to precipitate compounds with S²⁻ you would need to bubble it through the solution for effective reactions. With that, it is also toxic and smells like rotten eggs so using thioacetamide is a better and more viable option. The acidic environment suppresses the concentration of S²⁻ ions, ensuring that only Group II cations—with extremely small sulfide solubility products—precipitate, while later-group cations remain in solution. The resulting sulfides have a whole array of colors, however to actually be able to differentiate them we add Na₂S or (NH₄)₂S which will cause some metals to form soluble complexes with sulfur in them(As³⁺/As⁵⁺, Sb³⁺/Sb⁵⁺, Sn²⁺/Sn⁴⁺). Others will continue to stay insoluble(Cd²⁺, Cu²⁺, Bi³⁺, Hg²⁺). To differentiate between the insoluble compounds we can add hot nitric acid. This will cause all the cations except HgS to dissolve. The to further differentiate between Cd²⁺, Cu²⁺, Bi³⁺ we can add ammonia which then causes Cu²⁺ to form a deep blue that is easily identifiable. Bi³⁺ forms Bi(OH)₃ -white precipitate and Cd²⁺ forms a colorless solution. You may be thinking why can’t we identify Cu²⁺ before adding ammonia. Cu²⁺ can sometimes form a vibrant blue solution but sometimes the solution can be a very faint color so adding NH₃ is always safer and thus preferable in a lab setting.

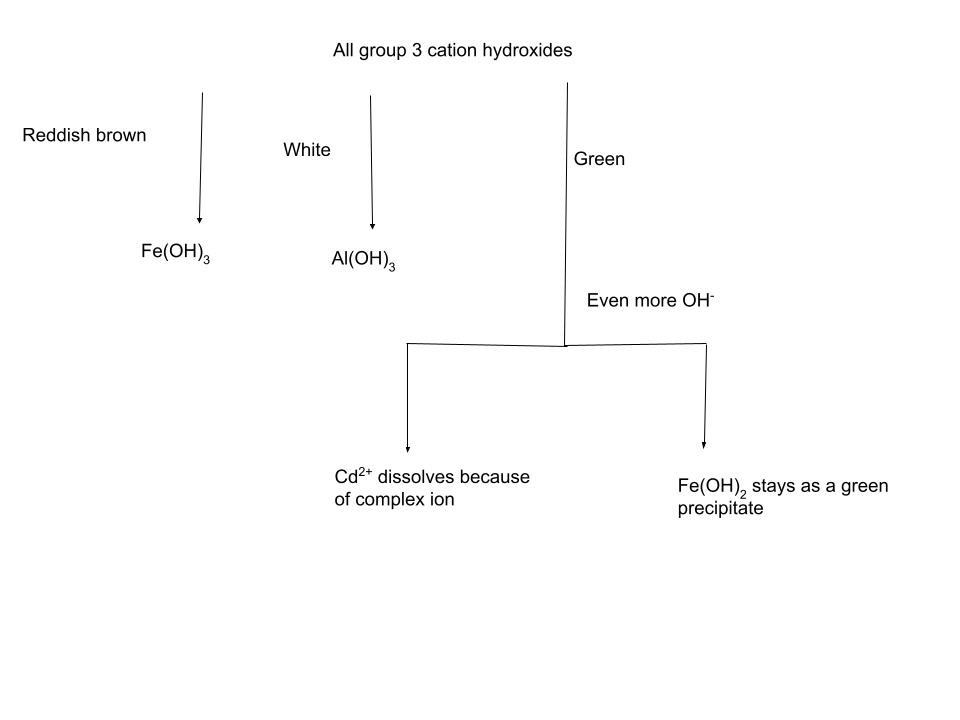

The third analytical group consists of cations that form insoluble hydroxides in the presence of a relatively low concentration of hydroxide ions. This group includes Fe²⁺, Fe³⁺, Al³⁺, and Cr³⁺. Upon addition of OH⁻,the resulting compounds can be identified through physical properties: a reddish-brown precipitate indicates the presence of Fe³⁺, a gelatinous white precipitate corresponds to Al³⁺, and a green precipitate suggests either Cr³⁺ or Fe²⁺. Because these two ions produce similarly colored precipitates, further differentiation is required. When excess hydroxide is added, Cr(OH)₃ dissolves, while Fe(OH)₂ remains insoluble.

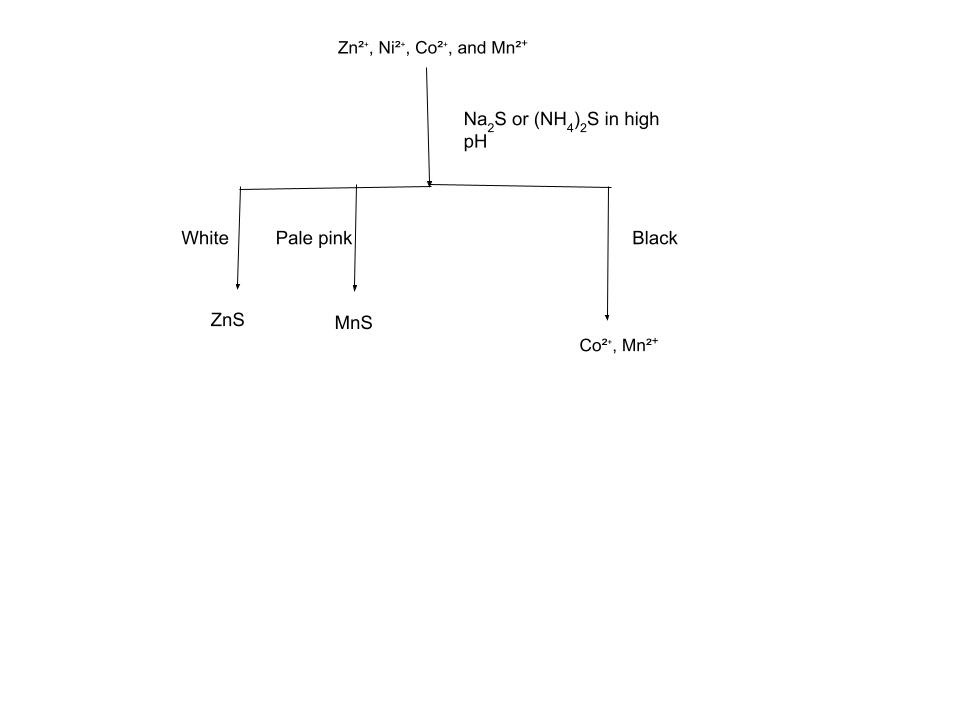

The 4th analytical group consists of Zn²⁺, Ni²⁺, Co²⁺, and Mn²⁺, which are identified by their ability to form sulfides in an alkaline environment (specifically at pH 9). To test for them, you use the same ammonia/ammonium chloride buffer from the Group 3 tests and add either ammonium sulfide or 0.1 M Na₂S. To differentiate between the compounds in group 4 we can use colors yet again. Zinc creates white ZnS, and manganese creates pale pink MnS. Both cobalt and nickel form black precipitates.

The 5th group is consists of the cations that are not soluble with carbonate. The most notable are Ba²⁺, Ca²⁺, and Sr²⁺ and they can be tested separately by their flame colors. And then the only elements that have not precipitated are Mg²⁺, Li⁺, Na⁺ and K⁺ (group 6 cations)since they have a low lattice energy and are highly soluble. To differentiate between these we can then again use flame tests.

Anion Analysis

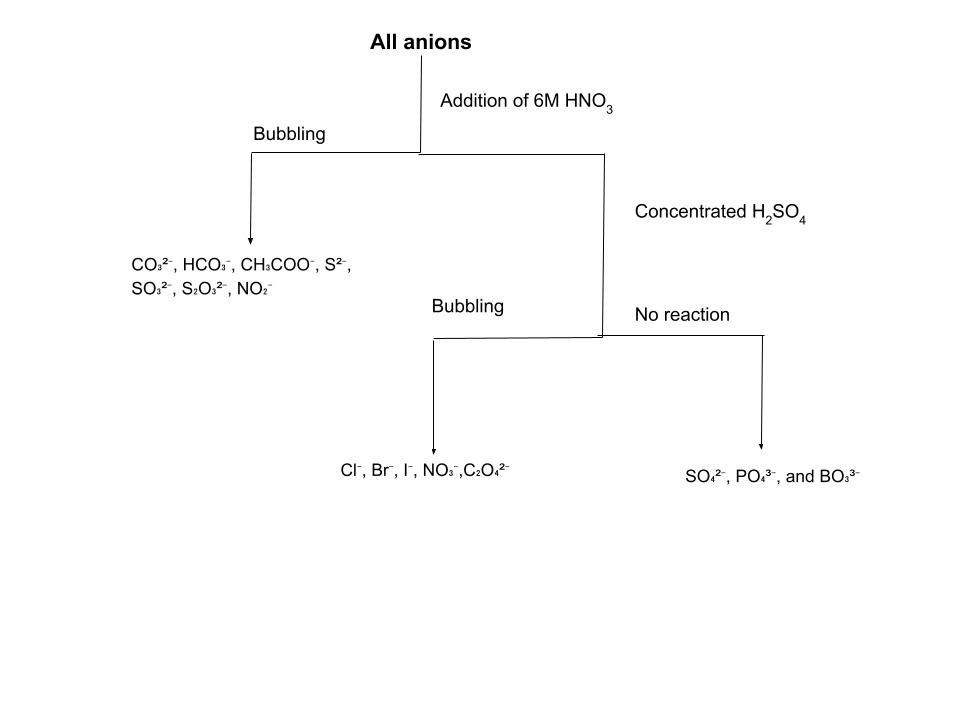

Anion analysis is the counterpart to cation analysis, focusing on the identification of negatively charged ions in solution. Unlike cation analysis, which rigidly separates ions into sequential groups based on precipitation, anion analysis often relies on "preliminary tests" involving dilute and concentrated acids. These tests exploit the tendency of certain anions to form volatile acids or distinct gases when protonated. By observing the effervescence, smell, and color of the evolved gases, we can narrow down the possibilities before moving to specific confirmatory tests.

1st Analytical Group of Anions

The first group of anions consists of those that react with dilute acids (like HCl or H₂SO₄) to release gases. This group includes CO₃²⁻, HCO₃⁻, CH₃COO⁻, S²⁻, SO₃²⁻, S₂O₃²⁻, and NO₂⁻. The testing procedure relies heavily on your sense of smell and observation of gas evolution.

When dilute acid is added, Carbonates (CO₃²⁻) react immediately with brisk effervescence, releasing colorless CO₂ gas. This gas turns limewater milky due to the formation of CaCO₃, though you must be careful not to pass the gas for too long, or the precipitate will dissolve back into soluble calcium bicarbonate. Sulfides (S²⁻) are perhaps the easiest to identify because they release H₂S, which smells distinctly of rotten eggs. To confirm this, we use lead(II) acetate paper, which turns black as PbS forms.

Sulfites (SO₃²⁻) and Thiosulfates (S₂O₃²⁻) both produce SO₂ gas, which smells sharply of burning sulfur. To distinguish them, look for the solution appearance: thiosulfates also produce a cloudy white precipitate of elemental sulfur, whereas sulfites do not. Finally, Nitrites (NO₂⁻) are identified by the release of reddish-brown NO₂ fumes that turn starch-iodide paper blue, and Acetates (CH₃COO⁻) release a vinegar smell (acetic acid) upon heating, which can be confirmed by the blood-red color produced with FeCl₃.

2nd Analytical Group of Anions

The second analytical group consists of anions that do not react with dilute acid but decompose or react when treated with concentrated sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄). This group consists of Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻, NO₃⁻, and C₂O₄²⁻. The Halides (Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻) are often initially tested with silver nitrate. Chloride forms a white precipitate, Bromide a pale yellow one, and Iodide a yellow one. Since these colors can be hard to distinguish, we use specific confirmatory tests. For Chlorides, the definitive method is the Chromyl Chloride test: heating the salt with K₂Cr₂O₇ and concentrated acid produces red vapors that eventually lead to a yellow lead chromate precipitate. For Bromides and Iodides, we use the "layer test" by adding chloroform (CHCl₃) or CS₂. An orange layer confirms Bromine, while a violet layer confirms Iodine. Nitrates (NO₃⁻) are identified by the famous "Brown Ring Test." When FeSO₄ is added to the nitrate solution and concentrated sulfuric acid is carefully poured down the side of the tube, a brown ring of [Fe(NO)]²⁺ forms at the interface of the liquids. Lastly, Oxalates (C₂O₄²⁻) evolve both CO₂ and CO gases; the CO burns with a blue flame, and the oxalate ion can distinctively decolorize purple KMnO₄ solution.

3rd Analytical Group of Anions

The third analytical group consists of SO₄²⁻, PO₄³⁻, and BO₃³⁻. These anions are unique because they generally do not react with either dilute or concentrated sulfuric acid to produce gases. Instead, we rely entirely on precipitation reactions. Sulfates (SO₄²⁻) are identified by adding BaCl₂, which forms a dense white precipitate of BaSO₄. This precipitate is chemically robust and insoluble in any acid or base. Phosphates (PO₄³⁻) are confirmed by adding nitric acid and ammonium molybdate; upon heating, a characteristic yellow crystalline precipitate forms. Borates (BO₃³⁻) are identified using a flame test: when the salt is mixed with concentrated sulfuric acid and ethanol and then ignited, volatile ethyl borate forms, causing the flame to burn with a distinct green edge.