Transition Metal Chemistry

Transition metals are known for their variable oxidation states, formation of colorful compounds, and unique ability to form complex ions. Unlike main-group metals, transition metals have partially filled d-orbitals, which gives rise to rich chemistry involving coordination compounds, redox reactions, and catalytic activity. These elements play crucial roles not only in laboratory and industrial chemistry but also in biological systems, such as the iron in hemoglobin or the cobalt in vitamin B12. Studying transition metal chemistry helps us understand why compounds exhibit specific colors, magnetic properties, and reactivity patterns, making it a central pillar of inorganic chemistry.

Structure of Transition metal complexes:

Transition metal complexes are chemical species with a transition metal at the center, surrounded by ligands. Ligands are molecules or ions that donate electron pairs to the metal, and they can attach to the metal through one or more donor atoms. The way ligands connect to the central metal is called denticity. A monodentate ligand binds to the metal at a single site, a bidentate ligand binds at two sites, and a polydentate ligand binds at more than two sites. The amount of actual bonds that the transition metal shows is called the coordination number.

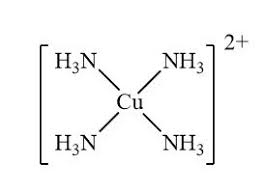

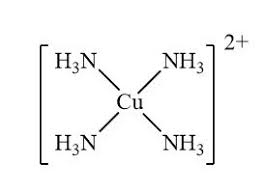

Notice how in this example, the ligands only have one bond with the transition metal. Thus, these ligands are called monodenature. The coordination number of this compound would be 4 since the Cu in the middle forms 4 bonds with ligands. There are no counter ions in the diagram present but we can expect there to be some counter ions that together will have a 2- charge.

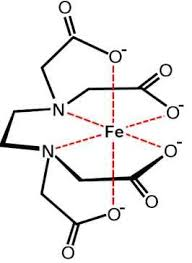

Ligands with multiple binding sites can form rings with the metal, which often makes the complex more stable—a phenomenon known as the chelate effect. A very important polydentate ligand is known as EDTA and it binds all around the transition metal in 4 areas and can enclose off the actual metal in the center. An example of this is, [Fe(EDTA)]2-⁻. All 6 ligands of the iron are bound to EDTA. Notice that these transition metal complexes also commonly have charges. To balance these charges in solutions counter-ions are used which do not actually bind to the charge but instead just close to the complex to balance slightly.

Oxidation state of the Transition metal in the center:

Calculating the oxidation state of the transition state is straightforward and simple. The first step is just to assume all the ligands have the electrons form the bonds that they form with the transition metal. This works because metals are very electropositive and therefore the ligands are more stable with the electrons from the complex. Then calculate the total charge of all the following ligands. Then we can simply use the formula below to calculate the charge of the transition metal in the middle.

total ligand charge + metal charge = overall charge

Let's take an example of the complex below. If we assume that all the electrons from the bonds with the ligands and the center metal will reside in the NH3(ligand) then we see that the charges of all the NH3 will be 0. Applying the formula above we can see that the oxidation state of the Cu is 2+

Stereoisomerism

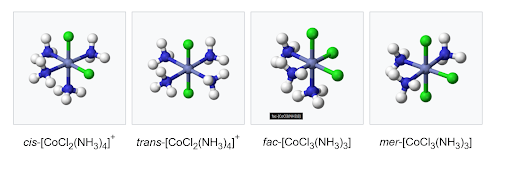

Cis–trans isomerism happens in octahedral and square planar complexes, but not in tetrahedral ones. If two identical ligands are next to each other, the complex is called cis; if they are opposite each other, it is called trans. In octahedral complexes with three identical ligands on one face, the isomer is called facial (fac). In a fac isomer, any two identical ligands are always adjacent (cis). If the three ligands and the metal lie in the same plane, the isomer is called meridional (mer). A mer isomer has a mix of cis and trans pairs, so it can be thought of as part cis, part trans.

Crystal Field Theory: CFT

Crystal Field Theory (CFT) is a model used to explain the behavior of transition-metal complexes by describing how ligands interact with the metal ion’s d orbitals. It treats metal–ligand bonding as primarily electrostatic, where approaching ligands cause repulsion between their electron pairs and the metal’s d electrons, leading to a splitting of the d-orbital energy levels. This splitting is crucial because it determines how electrons are arranged within the orbitals. Crystal Field Theory is useful because it helps explain important chemical properties such as the color of coordination compounds, their magnetic behavior, and whether a complex is high spin or low spin. By relating structure to observable properties, CFT provides a powerful framework for predicting and interpreting the behavior of transition-metal complexes in both laboratory and real-world chemical systems.

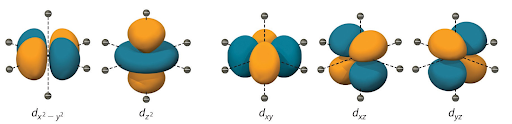

In an octahedral setting there are 6 ligands arranged in an octahedral format so the d-orbitals that have the least overlap with the ligand to metal bonds are the lowest in energy. These d-orbitals that are not overlapping with the axis are known as dxy dxz, or dyz orbitals. These orbitals are lower in energy than the dz² or dx²-y² which do have overlap with the bonds inside the transition metal complex. Below is the image of all the electron orbitals and we can see that any of the orbitals that overlap with the axis will have a higher energy than the ones that do not overlap the axis. The axis is where we assume the ligand bonds to be in Crystal Field Theory.

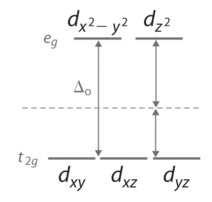

In an energy diagram we see this as a split in the energy between the less overlap(t2g) orbitals and the more overlapped(eg) orbitals.

From the Aufbau principle the electrons will fill up the lower energy orbitals first and then move on to filling up the higher energy orbitals. And according to the Hund’s rule, each electron will fill the orbitals in the same energy level before pairing up. When an electron is alone in an orbital that compound is called paramagnetic. When all the orbitals are paired up then the compound is known to be diamagnetic. For example if there are 4 d electrons in an octahedral compound then the dxy, dxz and dyz orbitals are all filled once then one electron is added to one of the orbitals at random. Then we are left with a paired d-orbital and 2 unpaired electron orbits. Thus d4 electron compounds are known to be paramagnetic. If we follow the same process we can see that d6 orbitals exhibit diamagnetism.

Tetrahedral compounds:

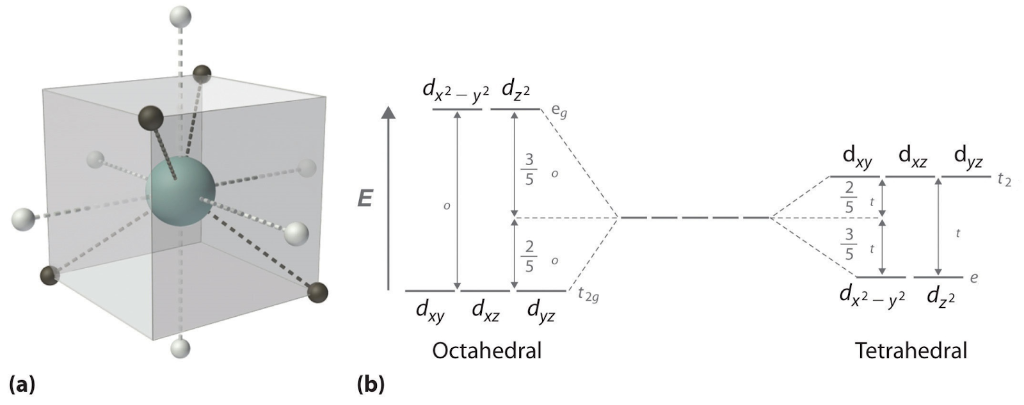

Through the exact same reasoning as for the octahedral compounds we can see that some orbitals overlap the bonds in the ligand more than other orbitals do.

In this case we can see that the dz² or dx²-y² orbitals overlap the least and so they will be the lowest in energy. The dxy dxz and dyz orbitals overlap the most so they are higher in energy. Using the same Aufbau principle and Hund’s rule we can predict the magnetic properties of the tetrahedral complex as well.

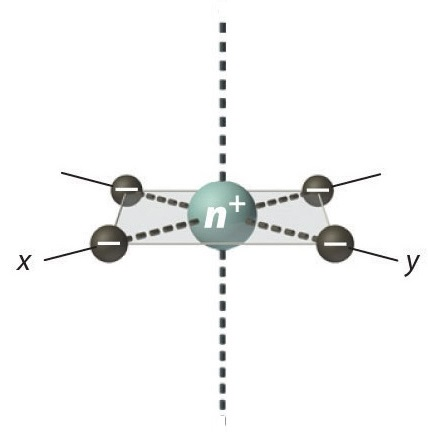

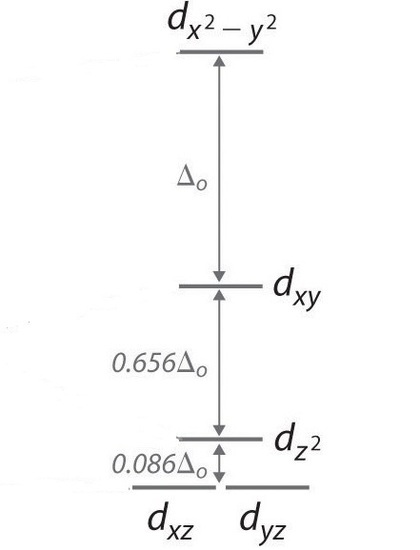

The last arrangement that we need to consider is the square planar configuration and it consists of ligands on the x and z axis so dyz and dxz are the lowest in energy followed by dz2 and then dxy and the highest being dx2-y2.

The spectrochemical series

Sometimes in compounds the Aufbau principle and the Hund’s principle are at odds with each other. Will the electron go in the same orbital and fight the repulsive forces with the other electrons or will it go to an orbital that is higher in energy. This question can be predicted by the use of the spectrochemical series which highlights which ligands cause a higher splitting energy and which ligands cause a lower splitting energy. The ones that cause a higher splitting energy prefer to pair up the electrons(low spin compounds) while compounds with a lower energy splitting will prefer the Aufbau principle and are said to have high spin. The spectrochemical series is as follows and it goes from lower energy splitting to higher energy splitting.

I⁻ < Br⁻ < S²⁻ < SCN⁻ < Cl⁻ < F⁻ < OH⁻ < H₂O < NCS⁻ < NH₃ < en < NO₂⁻ < CN⁻ < CO

The color of transition-metal complexes comes from the splitting of the metal’s d orbitals when ligands surround the central ion. This splitting creates an energy gap, known as the crystal field splitting energy (Δ), between lower- and higher-energy d orbitals. When visible light strikes the complex, electrons can absorb specific wavelengths of light that match this energy gap and are promoted from lower to higher orbitals in a process called a d–d transition. Because only certain wavelengths are absorbed, the remaining light is transmitted or reflected, and this complementary color is what is observed. The exact color of a complex depends on the magnitude of Δ, which is influenced by factors such as the nature of the ligand, the oxidation state of the metal ion, and the geometry of the complex. Strong-field ligands produce a larger splitting and typically result in absorption of higher-energy light, while weak-field ligands cause smaller splitting and absorb lower-energy light. Thus, variations in crystal field splitting explain why transition-metal compounds display a wide range of colors. Up next are some of the key colors that you must know.

- [Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻ (ferrocyanide) → yellow

- [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻ (ferricyanide) → red-brown

- [Fe(SCN)]²⁺ → blood red

- [Cu(H₂O)₆]²⁺ → pale blue

- [Cu(NH₃)₄]²⁺ → deep royal blue

- [Co(H₂O)₆]²⁺ → pink (octahedral)

- [CoCl₄]²⁻ → blue (tetrahedral)

- [Ni(H₂O)₆]²⁺ → green

- [Ni(NH₃)₆]²⁺ → blue-violet

- [Cr(H₂O)₆]³⁺ → violet

- [Cr(OH)₆]³⁻ → green

- MnO₄⁻ → deep purple

- [Ag(NH₃)₂]⁺ → colorless (complex ion, dissolves AgCl)

- [Zn(OH)₄]²⁻ → colorless

- [Al(OH)₄]⁻ → colorless

Complex ion and their effect on solubility

The formation of complex ions will lower the concentration of the ions so that more of the precipitate will then redissolve. This is very common and this is how a lot of precipitates are commonly dissolved in aqueous solutions. Ammonia is the most common ligand to do this and it forms transition metal complexes with silver. copper, zinc and nickel so it can be used to dissolve precipitates that contain these cations. Another important ligand used to dissolve precipitates is OH-. Addition of excess base will cause the concentration of OH- to go up and therefore precipitate to redissolve. Cations that exhibit this property are Al, Zn, Cr and Pb. This is in fact a common cation test to see if any of these compounds are present (Adding OH- will cause these compounds to precipitate and then they will redissolve again.) Cl- is another ligand that we should be aware of. It most commonly redissolves Pb2+ but can also redissolve Ag+. Recall that this is why we are unable to use a very high concentration of chloride when performing cationic analysis for the group 1 cations.